Why price-to-sales multiples are nonsensical: When is the price-to-sales ratio ever meaningful?

We often hear analysts mention price-to-sales multiples on CNBC and Bloomberg. Are such multiples meaningful? In most cases they are not. I’ll explain why using sales multiples can be nonsensical and often reveals ignorance about valuation and financial concepts.

The problem with price to sales is that it only takes into account one form of capital: the market capitalization of the common stock being traded. The company being valued could be significantly indebted and also might have preferred stockholders, minority interest holders, or have non-operating assets or investments that could be disposed of to generate cash that ultimately adds value to the company. That’s why enterprise value (EV), also known as firm value, is used for firm-wide financial measures like net sales, EBITDA, and EBIT, as opposed to equity-level earnings measures like pretax income and net income (better known as “earnings”).

Not Understanding Those Who Contributed Capital to the Firm

By firm-wide financial measures, we are talking about revenue or earnings streams that are before debtholder obligations and interest expense: these are net sales, gross profit, EBITDA and EBIT. When Wall Street types talk about “earnings”, they are really talking about net income, that is earnings after taxes. That earnings measure has been stripped of interest expense to meet debtholder obligations and taxes to meet the obligations of taxing jurisdictions. Net income, then, is a residual financial measure that accrues to common stockholders. That’s what trickles down to those holding the common stock: the return to such stockholders is scalable when the going is good — as long as you clear the hurdle by meeting debt obligations, anything remaining accrues to the common stockholder. However, when you can’t meet debt obligations and eventually have to declare bankruptcy, usually you’re left with nothing.

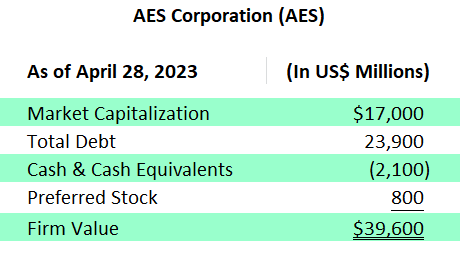

Think about how a company generates its annual net sales. For example, before a regulated utility or power company can generate sales, it needs a power purchase agreement to build a plant. That plant is usually majority-financed through debt financing. It is not unusual to find utility companies that have 50-50 or 75-25 debt-to-market equity proportion. In other words, debt was the majority contributor to revenue generation and has to be taken into account. Take AES Corp., a utility company based in the Washington, D.C. area. The company has $17 billion in market cap, $23.9 billion in total debt, and $2.1 billion in cash. The firm value would be 17 + 23.9 - 2.1 = 38.8, right? Well, the enterprise value of AES also has another component. There is about $800 million in carrying value of preferred stock. So firm value is 38.8 + 0.8 = $39.6 billion.

Those are the investors that have put capital into the company. It’s not just common stockholders — they only account for 43% of the total capital invested.

Sales Multiple for the Entire Firm or Each Capital Holder?

Let’s calculate the sales multiple: LTM net sales is $12.6 billion. So what is price to sales? 17.0 / 12.6 = 1.35x. That seems reasonable, right? Well, that only takes into account 43% of the capital holders in AES. So what is the debt-to-sales ratio? 21.8 / 12.6 = 1.73x. What is the preferred-to-sales ratio? 0.8 / 12.6 = .06x. Add them all together: 1.35 + 1.73 + .06 = 3.14, which is equal to EV / revenue = 39.6 / 12.6 = 3.14x.

This is the governing metric or the numerator of the company in calculating valuation multiples. The company is an “enterprise” with 3 capital holders that invested in the company and each have their own obligations. First, there is the debtholder which will get interest payments: that comes before the payment of taxes and acts as a tax shield for the company. Then comes preferred stockholders who may be due preferred dividends. Then whatever is remaining proportionally accrues to those holding the company’s common stock trading on the open market.

What is the “sales yield” for the company? Once again, LTM net sales is $12.6 billion and enterprise value is $39.6 billion. We calculated the sales multiple for the enterprise at 3.14x. So 1 / 3.14 = 31.8%. What this literally means is that each dollar provided by all 3 capital holders is responsible for 31.8 cents of revenue. I am showing this example since many guests that appear on CNBC and Bloomberg invert the P/E multiple and claim to derive “earnings yield” for the stock. Well, what is the “sales yield” for the price-to-sales multiple, then? Is it price to sales (17 / 12.6) divided by 1 = 74 cents?

From Sales Multiple to Sales Yield

No, that’s assuming only the common stockholder exists and you can tell right away that’s way too high. The common equity capital only accounts for 43% of the total: so it’s 43% times the sales yield for the enterprise derived above or 43% x 31.8% = 13.7%. Which seems right. Each dollar invested in the common stock contributes 13.7 cents of revenue.

Returning to price to sales, are there any instances when the price-to-sales multiple is meaningful? When valuing 100% common equity companies like tech and biotech stocks that have zero debt and no earnings, negative EBITDA? Well, even in this case, dividing the common equity market cap by LTM sales could still lead to misleading multiples. That’s because the market cap includes cash and cash equivalents unlike enterprise value that is usually calculated net of cash. Usually, these tech and biotech companies are flush with cash from financing rounds or IPOs.

Why Cash Distorts Valuation Multiples

Some people have noticed the practice of subtracting cash from debt and think that’s because cash offsets debt dollar for dollar. Is that really the reason? Well, that could be the reason for those who do it mechanically without much thinking. But cash may also qualify as needed working capital. The practice is really to derive the “operating value” of the company, i.e., the going concern value of the company. Cash is cash so the value of the company isn’t likely to fall beneath the cash balance. The point is to exclude that to derive the value of the company’s operations without the excess cash balance which overstates the multiple. This is essential when looking at similar companies and comparing their multiples, as the multiples will be distorted by huge cash balances. This why in some cases, when valuing tech or biotech companies with little or no debt, you end up with enterprise value that is smaller than the market cap because net debt happens to be negative (more cash than debt). Yes, the smaller enterprise value is the right numerator to divide LTM sales by.

The appropriate metric would be enterprise value over sales or market cap over sales but using market cap that is stripped of cash. In other words, it's really only meaningful if you subtract cash from the market cap when there is no debt. But the price-to-sales ratio wouldn't reflect that (raise your hand if you don't understand this). So even in this case, the price-to-sales ratio is a nonsensical measure.

The price-to-sales multiples tend to be used by financial journalists and those who want to overstate the metric to mask the excess cash balance and make the company they are promoting appear more valuable: business brokers, stock promoters, sellside research people , etc. It seems deceptively easy since it's just dividing one number by another. Why do you think journos with liberal arts backgrounds have gone full hog throwing around such multiples when talking about tech and biotech companies? They think they can divide and subtract. It doesn't require much thinking about what's behind the numbers.